By Newley Purnell and Eric Bellman

COLOMBO, Sri Lanka -- Days after bomb blasts killed more than

300 people across Sri Lanka, Facebook and other top social-media

platforms remained blocked in one of the largest experiments in

government control over social media. While some citizens said they

welcomed the restrictions, others said they had found

workarounds.

Security officials are worried the Easter Sunday morning attacks

-- which targeted churches and tourists across the country -- could

trigger rumors, backlash, riots or even retaliation. So the

government shut down Facebook, its WhatsApp and Instagram apps,

Google Inc's YouTube, and even Snap Inc.'s Snapchat to create a

speed bump for hate speech and false reports.

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe speaking to news media

Tuesday declined to say when the blocks would be lifted. "We went

through this exercise earlier," he said, referring to a similar

shutdown a year ago amid heightened interreligious tensions, "and

we didn't want to take another chance."

A Facebook Inc. spokeswoman didn't immediately respond to a

question about how long the block on its services might last. A

Google spokesman declined to comment. A spokeswoman for Twitter,

which remains accessible, didn't immediately respond to a request

for comment.

Pathmasiri Haputhanthiriga, the owner of a mobile-phone

accessories shop said the block had slowed his business by blocking

his regular use of WhatsApp to communicate, but he thought it was

worth the sacrifice. "For information, slower is better," he said,

referring to the blocks on the flow of social-media chatter after

the attacks.

Governments around the world and technology companies are

struggling to stem the flow of hate speech as well as false

information following abuses such as foreign interference in U.S.

elections. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has embraced stricter

content-moderation requirements and last month said global

regulators should take a "more active role" in governing the

web.

Extremists have used Facebook to stoke violence, including in

Sri Lanka and Myanmar. In India, the government has proposed

forcing WhatsApp to break encrypted messages to find people who

send objectionable content after more than 20 people were killed

last year in mob violence following rumors spread through the app.

A number of nations are focusing on gaps in social media companies'

monitoring of posts and are seeking to impose regulations on

them.

Sri Lanka has been a trailblazer in the battle rein in the

impact of social media. In March 2018 there was a flare up in

tensions between Muslims and Buddhists in some regions of the

country. People spread false reports and organized attacks through

social media, and the government sought ways to stop the spread of

violence.

Facebook, WhatsApp, YouTube and other platforms were blocked in

part or all of the country for days. The violence subsided. Many

felt the reaction was a heavy-handed move -- but it succeeded.

After Sunday's attacks, the government wasted no time in

blocking popular platforms again, according to NetBlocks, a

London-based digital-rights group, and other internet monitoring

groups. Facebook and other platforms remain inaccessible or too

sluggish to use, according to consumers.

Rizvi Arif, an Uber driver in Colombo who is Muslim, said he had

always felt safe in Sri Lanka but wondered what kind of backlash

misinformation could cause for his community. He has stopped going

to the mosque to pray, worried about retaliation from someone

misled by all the misinformation on the internet. His family now

just prays at home.

"I hate Facebook and WhatsApp," he said. "Sometimes, for

emergencies, it's OK" to block such platforms, he said.

To be sure, rumors have still spread in the wake of bombings,

but via word of mouth or television, users note. One rumor that

circulated online incorrectly claimed that the safe demolition of a

bomb by police was an attack. Another rumor spread by word of mouth

claimed that drinking water in the country had been poisoned.

People have been circumventing the government blocks by using

virtual private networks, or VPNs, which reroute traffic so

authorities can't tell where users are logging on from.

University student Mohammed Afrid said he is ignoring government

government suggestions not to use VPNs and employing one to get the

latest news and interact with others. "We need them to get

information" about what's happening following the attacks, he said.

"Without communication, it's like my body doesn't work."

One of the hardest-hit churches -- St. Sebastian's church which

lost more than 100 worshipers in the attack -- decided to use a VPN

to post photos of the destruction on its Facebook page to ask for

help and prayers.

"I just got a VPN because all social media is blocked," said the

Rev. Edmond Tillekeratne, social communications director for the

Archdiocese of Colombo."The truth has to go out."

Some are finding a silver lining in the crackdown. Mr.

Haputhanthiriga, the shop owner, said his daughters are typically

glued to their smartphones but have been forced into old-fashioned

social interaction.

"They are talking now," he said, smiling. "We get to have a

conversation."

Write to Newley Purnell at newley.purnell@wsj.com and Eric

Bellman at eric.bellman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 23, 2019 13:26 ET (17:26 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

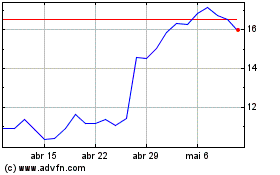

Snap (NYSE:SNAP)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Mar 2024 até Abr 2024

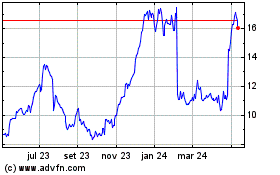

Snap (NYSE:SNAP)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Abr 2023 até Abr 2024