By Stu Woo and Asa Fitch

In terms of technology, the world had been unifying for years.

Now it is reverting back to the likes of the VHS-versus-Betamax

era, with much bigger consequences.

Imagine two countries with completely different sets of hardware

and software for the internet, electronic devices,

telecommunications, and even social media and dating apps.

That is the direction the U.S. and China are headed in -- a

world where the two global powers have mutually exclusive

technology systems.

The wedge being driven between the two countries alarms tech's

biggest names, with the likes of Microsoft Corp. co-founder Bill

Gates and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. co-founder Jack Ma calling it

counterproductive for both sides. While this month's signing of a

phase-one trade deal between the U.S. and China may have eased

broad, short-term economic concerns, deeply held suspicions in both

countries suggest the technology gap will only widen in the coming

decade.

A battle that had centered on the telecom industry, with the

U.S. effort to globally blacklist Chinese giant Huawei Technologies

Co. over fears of potential spying and cyberattacks, has burst into

a much wider conflict that has altered virtually every part of the

technology sector on both sides of the Pacific. Huawei has

responded by taking steps to divorce its entire supply chain from

the U.S.

China is hastening to make semiconductors and consumer

electronics without U.S. parts, after Washington restricted

American businesses from supplying Chinese companies. In social

media, the Trump administration in November opened an investigation

of Beijing-based ByteDance Inc., the maker of the hit video-sharing

app TikTok, over national-security concerns surrounding the

collection of users' personal data and the alleged censorship of

content critical of the Chinese government. That came after

Washington in March ordered a Chinese company, Beijing Kunlun Tech

Co. Ltd., to sell gay-dating app Grindr over fears that China could

use data from the app to blackmail Americans with security

clearances.

A TikTok spokesman cited an earlier statement saying that it

hadn't been asked by the Chinese government to censor content, and

that its content-moderation policies are free of any government

influence. Attempts to reach Kunlun for this article weren't

successful.

Driving the American side of this conflict are not only worries

about spying, cybersecurity and blackmail, but also concerns that

the U.S. is losing ground to Beijing in the race to develop and

implement the latest technology, including artificial

intelligence.

"The Trump administration has employed an expansive and novel

definition of national security to set back Chinese firms working

in everything from memory chips to social media," says Dan Wang, a

Beijing-based technology analyst for research firm Gavekal

Dragonomics. "Over the longer term, the strategic solution for

Chinese firms is straightforward: develop technology capabilities

so that they're not so dependent on U.S. supply."

Years of conflict

The history of the technological divide goes back at least a

decade, with China firing one of the first shots when it censored

search results from Google. The company essentially left the

Chinese market in 2010, thus beginning an era of two internets: one

for China and one for the rest of the world. With Google and

Facebook Inc. restricted in China, citizens there flocked to

homegrown giants, such as search-engine Baidu Inc. and WeChat,

Tencent Holdings Ltd.'s messaging, social-media and payment app.

Such Chinese tech giants help Beijing by censoring sensitive

content and monitoring the activities of Chinese citizens. Baidu

and Tencent didn't respond to requests for comment for this

article.

Telecom became the focal point in 2012, when Congress all but

banned Huawei from major U.S. business by concluding the Chinese

company couldn't refuse a hypothetical order from Beijing to spy or

conduct a cyberattack. Huawei denies that it could use its products

to spy or conduct cyberattacks on Beijing's behalf.

A year later, documents leaked by Edward Snowden alleged that

the National Security Agency could hack into telecom equipment made

by both Huawei, which relied on American components, and Silicon

Valley's Cisco Systems Inc. That could have spurred Beijing to move

Chinese companies away from U.S. dependence, analysts say.

These skirmishes finally exploded into a full-blown

technological battle shortly after President Trump took office in

2017. The confrontation had two fronts: trade and national

security. On trade, President Trump implemented tariffs on China

for its alleged unfair trade practices -- such as forcing U.S.

companies to share technology with Chinese ones in exchange for

access to the Chinese market, an issue that wasn't resolved by the

phase-one trade pact. As for national security, his administration

took steps to hinder Huawei and to slow Chinese advances in

technology, especially that with military applications. U.S.

officials have stressed that the scrutiny of Huawei, ByteDance and

some other companies is rooted in national-security issues that are

separate from trade.

"2017 was the first time that an administration began to take

this on seriously, in a way that would radically change things,"

says Robert Spalding, who served on the White House's National

Security Council from 2017 to 2018.

Concern in the U.S.

The White House tried to make it harder for Huawei to build its

equipment by restricting American suppliers from selling parts to

the company. It also tried to stanch the flow of cutting-edge

computer technology to China to hinder its ability to build the

first next-generation supercomputers.

Enmeshed in the global supply chain, many American tech

companies have opposed efforts to decouple the U.S. from China.

Semiconductor manufacturers, in particular, have a lot to lose in

the dust-up because China is both a manufacturing hub and a growing

market for computers, smartphones and other electronics containing

their chips. The U.S. exported about $7 billion of chips to China

in 2018, substantially more than it imported from China.

Putting the screws to trade is forcing China to develop its own

industry and seek new, non-U.S. suppliers -- things the country has

already started to do, hurting American chip makers' revenues.

Huawei recently managed to build a smartphone without U.S. parts --

a feat that would have been improbable a couple of years ago.

"There's definitely a bifurcation, and I think the U.S.

semiconductor companies are very concerned," says Handel Jones,

chief executive of International Business Strategies, a

semiconductor consulting firm in Los Gatos, Calif. "As the Chinese

companies strengthen, the pie available for U.S. companies gets

smaller."

The Trump administration, however, has largely ignored industry

concerns. After imposing a ban on trade with Huawei last year, it

allowed companies to apply for licenses to continue shipping to the

telecom giant. But many haven't been approved and decisions haven't

come quickly, according to people familiar with the process.

The battle lines are different in social media, where U.S.

suspicion focuses on China's alleged use of apps to spy and to

advance China's political agenda, such as blocking videos and posts

that portray Beijing negatively.

In that arena, the Trump administration has ratcheted up

pressure by threatening to undermine Chinese companies' bids to

build user bases in the U.S. The national-security review of TikTok

and the demand that Beijing Kunlun Tech sell Grindr are part of

that effort.

An inevitable split?

Even if the U.S. and China mend fences and end their

long-running trade dispute, analysts say mutual suspicion all but

guarantees the march toward a two-system tech world will continue.

China is developing its domestic semiconductor industry and may

compete with the U.S. in Europe and other markets. The U.S. might

exclude Chinese hardware and smartphone apps from its market -- and

try to convince allies to follow suit.

In such a world, the race for technological dominance could come

with high stakes, handing the winner a stronger economy and greater

global influence than it could gain in a more integrated

market.

Who will win the technology race, under any circumstances, is an

open question. China may be behind for now, but some observers say

it's quickly catching up on what may be the next front in this

race: It is pouring tens of billions of dollars into

artificial-intelligence research that could be key to the next

technological revolution.

Mr. Spalding, the former National Security Council member, says

one American concern about Chinese ownership of popular apps is

that it gives Chinese companies more data that they can use to

improve their artificial intelligence.

Mr. Jones of International Business Strategies emphasizes the

importance of AI to both countries. "AI is high on the priority

list, and we think AI is a major differentiator in areas like

autonomous driving, virtual reality, augmented reality and even

medicine," he says. "We think AI is going to be a key factor in

terms of who's going to win and lose in the next five to 10

years."

Mr. Woo is a Wall Street Journal reporter in Beijing. He can be

reached at stu.woo@wsj.com. Mr. Fitch is a Journal reporter in San

Francisco. Email asa.fitch@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 20, 2020 13:02 ET (18:02 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

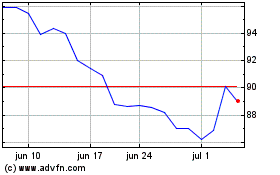

Baidu (NASDAQ:BIDU)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Mar 2024 até Abr 2024

Baidu (NASDAQ:BIDU)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Abr 2023 até Abr 2024