United States Securities and Exchange Commission

Washington, D.C. 20549

NOTICE OF EXEMPT SOLICITATION

Pursuant to Rule 14a-103

United States Securities and Exchange Commission

Washington, D.C. 20549

NOTICE OF EXEMPT SOLICITATION

Pursuant to Rule 14a-103

Name of the Registrant: BlackRock Inc.

Name of persons relying on exemption: The Shareholder Commons, Inc.

Address of persons relying on exemption: PO Box 7545, Wilmington, Delaware

19803-7545

Written materials are submitted pursuant to Rule 14a-6(g) (1) promulgated

under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Submission is not required of this filer under the terms of the Rule but is made voluntarily

in the interest of public disclosure and consideration of these important issues.

The

Impact of BlackRock’s Stewardship Practices on Clients and Shareholders: A Rebuttal to the BlackRock Board

We urge

shareholders to vote “FOR” Item 4 of the BlackRock Proxy

The Shareholder Commons urges you to vote “FOR”

Item 4, the shareholder proposal requesting that the Board of BlackRock Inc. (“BlackRock” or the “Company”) adopt

stewardship practices that prioritize economic risks to its diversified clients’ portfolios over individual company financial performance.

The Shareholder Commons is a non-profit advocate for diversified shareholders’

interests. We work with investors to stop portfolio companies from prioritizing financial return when doing so threatens the value of

diversified portfolios.

A. The

Proposal

The Proposal asks for BlackRock to steward its holdings so as to prioritize

diversified portfolio value over the financial returns of individual portfolio companies. Specifically, the proposal asks the shareholders

to approve the following resolution:

RESOLVED, shareholders ask that, to the extent practicable,

consistent with fiduciary duties, and otherwise legally and contractually permissible, the Company adopt stewardship practices designed

to curtail corporate activities that externalize social and environmental costs that are likely to decrease the returns of portfolios

that are diversified in accordance with portfolio theory, even if such curtailment could decrease returns at the externalizing company.

Diversified investors make up a large portion of BlackRock clients

and shareholders. The value of their portfolios is threatened by social and environmental costs created by individual companies in pursuit

of profit. In light of this tension between individual company value and portfolio value, the Proposal asks BlackRock to adopt stewardship

policies that balance these competing interests in favor of diversified investors.

BlackRock’s statement in opposition to the Proposal (the “Opposition

Statement”) admits that its stewardship policies prioritize the value of individual portfolio companies over diversified shareholder

returns, claiming it is legally required to do so. As we show below, this claim is wrong. Indeed, Staff of the Securities and Exchange

Commission rejected this same argument when BlackRock tried to exclude the Proposal from its Proxy Statement. The SEC Staff informed BlackRock

that it was “unable to conclude that the Proposal, if implemented, would cause the Company to violate federal law.”1

The Opposition Statement shows that the Company is operating under

the mistaken belief that its stewardship practices must always encourage companies to maximize their own individual returns. As we show

in this Rebuttal, that mistaken belief harms its diversified clients and is contrary to law. The requested change will help BlackRock

better protect its diversified clients from the social and environmental costs individual companies may create in pursuit of value maximization.

B. BlackRock

demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of its duty

BlackRock recently published its 2030 net zero statement, which claimed

that, as an asset manager, it had no responsibility to help decarbonize the economy:

BlackRock’s role in the [energy] transition is as

a fiduciary to our clients. Our role is to help them navigate investment risks and opportunities, not to engineer

a specific decarbonization outcome in the real economy.2

_____________________________

1 https://www.sec.gov/divisions/corpfin/cf-noaction/14a-8/2022/mcritchieblackrock040422-14a8.pdf

2 https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/about-us/our-2021-sustainability-update/2030-net-zero-statement

Yet decarbonizing the economy is possibly the greatest investment opportunity

available to BlackRock’s clients: preserving the Earth’s climate system is not separate from investing, it is a key value

driver. If BlackRock’s control over client assets creates the potential for it to help engineer real-economy decarbonization in

order to help those same clients, why would BlackRock choose not to pursue such an effort? As we show below, stewardship designed to reduce

greenhouse gas emissions and other corporate conduct that undermines diversified portfolio value falls squarely within BlackRock’s

duty as a fiduciary.

C. The

BlackRock Board recommends a vote against the Proposal, claiming it would be “inconsistent” with BlackRock’s “legal

duties”

The Opposition Statement suggests it would be illegal for BlackRock

to take any action that prioritized the financial performance of its clients’ diversified portfolios over the financial performance

of an individual portfolio company:

[T]he proponent wants BlackRock to adopt stewardship policies

with the goal of “directly support[ing] the health of social and environmental systems,” rather than focusing on individual

companies. In our view, shifting BIS’ [BlackRock Investment Stewardship’s] policies to examine macroeconomic systems in order

to benefit “diversified shareholders” would be inconsistent with our responsibility to our clients, and our legal duties,

and create legal risks for BlackRock and our shareholders.

By saying the Proposal is illegal, BlackRock is claiming it cannot

steward portfolio companies in a manner that might harm a single portfolio company’s individual financial performance, even if doing

so would benefit the portfolios of its clients. In other words, when BlackRock decides whether it should urge a portfolio company to reduce

its carbon footprint or pay workers a living wage, it only considers whether doing so will increase that single company’s enterprise

value. In contrast, BlackRock gives no further consideration to the impact of any external environmental or social impacts, even

when those impacts harm the portfolios of its own clients or even the very BlackRock funds that own those companies. This

self-imposed limitation has significant consequences: as one of the world’s largest asset managers, with about $10 trillion in assets

under management, BlackRock can influence the external social, environmental, and economic impact of its portfolio companies.

As discussed in the next two sections, this absolutist position is

harmful to all BlackRock’s diversified clients (as well as its diversified shareholders) and has no basis in law.

D. BlackRock’s

clients would benefit if it stopped prioritizing the financial value of individual portfolio companies

1. Investors

must diversify to optimize their portfolios

It is commonly understood that investors are best served by diversifying

their portfolios.3 Diversification allows them to reap the increased returns available from risky securities while greatly

reducing that risk.4

This core principle is reflected in federal law, which requires fiduciaries

of federally regulated retirement plans (included among BlackRock clients) to “diversify[] the investments of the plan.”5

Similar principles govern other investment fiduciaries.6 The late John Bogle—founder of Vanguard, another large asset

manager—summarized the wisdom of a diversified investment strategy: “Don’t look for the needle in the haystack; instead,

buy the haystack.”7 And, of course, many of BlackRock’s funds are themselves broadly diversified, offering its

clients an opportunity to take advantage of portfolio theory.

2. The

performance of a diversified portfolio largely depends on overall market return

Diversification is thus required by accepted investment theory and

imposed by law on investment fiduciaries. As a consequence, many BlackRock clients are largely diversified at the level of their entire

portfolio. Once a portfolio is diversified, the most important factor determining return will not be how the companies in that portfolio

perform relative to other companies (“alpha”), but rather how the market performs as a whole (“beta”).

In other words, the financial return to such diversified investors

chiefly depends on the performance of the market, not the performance of individual companies. As one work describes this, “[a]ccording

to widely accepted research, alpha is about one-tenth as important as beta [and] drives some 91 percent of the average portfolio’s

return.”8 Despite this fundamental truth, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink promised in his most recent letter to shareholders

to “keep alpha at the heart of BlackRock.”9 It is hard to fathom how focusing on a factor that drives only 9 percent

of the average portfolio’s return constitutes the best possible service to clients. Indeed, the Net Zero Asset Owners Alliance,

a United Nations-convened consortium representing more than $10 trillion in portfolio assets, recently said that “pursuing alpha

should not be prioritized in a silo that ignores the potential impact of market beta on asset owner returns” and called for investors

to “challenge alpha’s primacy as a performance measure.”10

_____________________________

3 See generally, Burton G. Malkiel, A

Random Walk Down Wall Street, W. W. Norton & Company (2016).

4 Id.

5 29 USC Section 404(a)(1)(C).

6 See Uniform Prudent Investor Act, § 3 (“[a]

trustee shall diversify the investments of the trust unless the trustee reasonably determines that, because of special circumstances,

the purposes of the trust are better served without diversifying.”)

7 John C. Bogle, The Little Book of Common Sense

Investing: The Only Way to Guarantee Your Fair Share of the Stock Market, John Wiley and Sons (2007) 86.

8 Stephen Davis, Jon Lukomnik, and David Pitt-Watson, What

They Do with Your Money, Yale University Press (2016).

9 https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-chairmans-letter

10 Jake Barnett and Patrick Peura, “The Future of

Investor Engagement: A Call for Systematic Stewardship to Address Systemic Climate Risk,” UNEP FI and PRI (April 2022), available

at https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/NZAOA_The-future-of-investor-engagement.pdf.

As shown in the next section, the social and environmental impacts

of individual companies can have a significant impact on beta.

3. Costs

companies impose on social and environmental systems heavily influence beta

Over long time periods, beta is influenced chiefly by the performance

of the economy itself, because the value of the investable universe is equal to the portion of the productive economy that the companies

in the market represent.11 Over the long run, diversified portfolios rise and fall with GDP or other indicators of the intrinsic

value of the economy. As the legendary investor Warren Buffet puts it, GDP is the “best single measure” for broad market valuations.12

But the social and environmental costs created by companies pursuing

profits can burden the economy. For example, if increases in atmospheric carbon concentration stay on the current trajectory, rather than

aligning with the Paris Accords, GDP could be 10 percent lower by 2050.13 With that backdrop, BlackRock’s assertion (quoted

above) that its role is “not to engineer a specific decarbonization outcome in the real economy”14 begins to look

like an abdication of its duty to clients.

More immediately, the difference between an efficient response to COVID-19

and an inefficient one could create a $9 trillion swing in GDP.15 Contributions to inequality also reduce GDP over time.16

_____________________________

11 Principles for Responsible Investment & UNEP Finance

Initiative, Universal Ownership: Why Environmental Externalities Matter to Institutional Investors, Appendix IV, available at https://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/documents/universal_ownership_full.pdf.

12 Warren Buffett and Carol Loomis, “Warren Buffett

on the Stock Market,” Fortune Magazine (December 10, 2001), available at https://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2001/12/10/314691/index.htm.

13 Swiss Re Institute, “The Economics of Climate Change:

No Action Not an Option” (April 2021) (Up to 9.7% loss of global GDP by mid-century if temperature increase rises on current trajectory

rather than Paris Accords goal), available at https://www.swissre.com/dam/jcr:e73ee7c3-7f83-4c17-a2b8-8ef23a8d3312/swiss-re-institute-expertise-publication-economics-of-climate-change.pdf.

14 Supra n.2.

15 Ruchir Agarwal and Gita Gopinath, “A Proposal to

End the COVID-19 Pandemic,” IMF Staff Discussion Note (May 2021), available at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2021/05/19/A-Proposal-to-End-the-COVID-19-Pandemic-460263.

16 Dana Peterson and Catherine Mann, “Closing the

Racial Inequality Gaps: The Economic Cost of Black Inequality in the U.S.” Citi (2020) (closing racial gaps could lead to $5 trillion

in additional GDP over five years), available at https://ir.citi.com/%2FPRxPvgNWu319AU1ajGf%2BsKbjJjBJSaTOSdw2DF4xynPwFB8a2jV1FaA3Idy7vY59bOtN2lxVQM%3D;

Economic Policy Institute, “Inequality is Slowing U.S. Economic Growth” (December 12, 2017) (Inequality reduces demand by

2-4% annually), available at https://www.epi.org/publication/secular-stagnation.

The acts of individual companies (including those in BlackRock portfolios)

affect whether the economy will bear these costs: if they increase their own bottom line by emitting extra carbon, refusing to share technology

that would slow the pandemic, or contributing to inequality, the profits earned for their shareholders may be inconsequential in comparison

to the added costs the economy bears.

Economists have long recognized that profit-seeking firms will not

account for costs they impose on others, and there are many profitable strategies that harm stakeholders, society, and the environment.17

Indeed, in 2018, publicly listed companies around the world imposed social and environmental costs on the economy with a value of $2.2

trillion annually—more than 2.5 percent of global GDP.18 This cost was more than 50 percent of the profits those companies

reported.

When the economy suffers from these “externalized” costs,

so do diversified shareholders. Thus, through impact on beta, diversified shareholders internalize social and environmental costs that

individual companies can profitably externalize, as shown in Figure 1.

_____________________________

17 See, e.g., Kaushik Basu, Beyond the Invisible

Hand: Groundwork for a New Economics, Princeton University Press (2011), p.10 (explaining the First Fundamental Theorem of Welfare

Economics as the strict conditions (including the absence of externalities) under which competition for profit produces optimal social

outcomes).

18 Andrew Howard, “SustainEx: Examining the social

value of corporate activities,” Schroders (2019), available at https://www.schroders.com/en/sysglobalassets/digital/insights/2019/pdfs/sustainability/sustainex/sustainex-short.pdf.

Figure 1

When BlackRock’s stewardship policies lead portfolio companies

to externalize costs, it is making a trade that affects its clients. For example, if BlackRock did not object to a portfolio company saving

costs with cheaper, carbon-intense energy, it might trade away climate mitigation (which supports the intrinsic value of the economy)

in exchange for more internal profit at the individual company. While this trade might financially benefit a shareholder with shares only

in that company, it harms BlackRock’s diversified clients (and its own diversified funds) by threatening beta.

By turning a blind eye to portfolio effects, BlackRock is simply ignoring

the best interests of its many diversified clients (and threatening the value of the diversified portfolios of its own shareholders).

Indeed, for these investors, the systemic impacts a company has on beta swamp the significance of alpha:

It is not that alpha does not matter to an investor (although

investors only want positive alpha, which is impossible on a total market basis), but that the impact of the market return driven by

systematic risk swamps virtually any possible scenario created by skillful analysis or trading or portfolio construction.19

_____________________________

19 Jon Lukomnik & James P. Hawley, Moving beyond

Modern Portfolio Theory: Investing that Matters, Chapter 5, Routledge (April 30 2021) (emphasis added).

E. The

relationship between beta and diversified portfolio performance demands attention from BlackRock

For all the reasons discussed in the prior sections, diversified investors

need protection from their own portfolio companies that externalize social and environmental costs. Diversified investors internalize

the collective costs of such externalities (more than $2 trillion from listed companies in 2018 according to the Schroders report cited

above20) because they degrade the systems upon which economic growth and corporate financial returns depend.

PRI, an investor initiative to which BlackRock is a signatory and whose

members have $120 trillion in assets under management, recognizes this need. It recently issued a report (the “PRI Report”)

highlighting corporate practices that can boost individual company returns while threatening diversified investors:

A company strengthening its position by externalising costs

onto others. The net result for the [diversified] investor can be negative when the costs across the rest of the portfolio (or

market/economy) outweigh the gains to the company…21

Because investors vote on directors and other matters, they have the

power and responsibility to steward companies away from such practices. PRI went on to describe the investor action necessary to manage

social and environmental systems:

Systemic issues require a deliberate focus on and prioritisation

of outcomes at the economy or society-wide scale. This means stewardship that is less focused on the risks and returns of individual

holdings, and more on addressing systemic or ‘beta’ issues such as climate change and corruption. It means prioritising

the long-term, absolute returns for universal [i.e., long-term, broadly diversified] owners, including real-term financial and welfare

outcomes for beneficiaries more broadly.22

_____________________________

20 Supra, n.17.

21 PRI, “Active Ownership 2.0: The Evolution Stewardship

Urgently Needs” (2019) (emphasis added), available at https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=9721. See also “Addressing

Climate as a Systemic Risk: A call to action for U.S. financial regulators,” Ceres (June 1, 2020), available at https://www.ceres.org/resources/reports/addressing-climate-systemic-risk.

(“The SEC should make clear that consideration of material environmental, social and governance (ESG) risk factors, such as climate

change, to portfolio value is consistent with investor fiduciary duty.”) Ceres is a non-profit organization with an investor network

with more than $29 trillion under management.

22 Ibid (emphasis added).

This is the refocusing the Proposal seeks. Moreover, BlackRock’s

fiduciary duties can require such refocusing of stewardship efforts. A new report from the law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer (the

“Freshfields Report”) explores fiduciary duty in eleven jurisdictions, including the United States, and explains how externalized

costs affect investment trustees’ fiduciary duties:

System-wide risks are the sort of risks that cannot be mitigated

simply by diversifying the investments in a portfolio. They threaten the functioning of the economic, financial and wider systems on which

investment performance relies. If risks of this sort materialised, they would therefore damage the performance of a portfolio as a whole

and all portfolios exposed to those systems.23

The Freshfields Report goes on to suggest that alpha-oriented strategies

(e.g., the strategies that BlackRock says it uses exclusively) are of limited value to diversified shareholders, and that beta focus is

the best way for investors to improve performance:

The more diversified a portfolio, the less logical it

may be to engage in stewardship to secure enterprise specific value protection or enhancement. Diversification is specifically intended

to minimise idiosyncratic impacts on portfolio performance…

Yet diversified portfolios remain exposed to nondiversifiable

risks, for example where declining environmental or social sustainability undermines the performance of whole markets or sectors…

Indeed, for investors who are likely to hold diversified portfolios in the long-term, the question is particularly pressing since these

are likely to be the main ways in which they may be able to make a difference.24

A Columbia Law professor stated that failing to focus on portfolio

effects means failing to maximize returns:

But engagements aimed at reducing systematic risk do not

run afoul of the “exclusive benefit” criterion [i.e., the rule that fiduciaries must protect their beneficiaries]; rather

they are in service to it. Indeed, pension fund managers who are not thinking about the systematic dimension in their engagements are

falling short of the objective of maximizing risk-adjusted returns.25

YUM! Brands, a publicly traded company in which BlackRock holds 8.4

percent of common stock,26 recently published a report describing the commercial pressures it faces when asset managers such

as BlackRock encourage it to maximize internal financial returns:

| · | “[Antimicrobial resistance (“AMR”)] is a significant healthcare challenge facing society

today. AMR impacts are not only measured in direct and indirect financial costs, but also in the cost of human lives and other societal

costs… This research appears to show that one of the most significant barriers to meeting the challenge of AMR is the balance

between the rewards of proactive AMR mitigation and the cost of changing established husbandry practices.” |

_____________________________

23 Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, “A Legal Framework

for Impact: Sustainability Impact in Investor Decision-Making” (2021), available at https://www.freshfields.us/4a199a/globalassets/our-thinking/campaigns/legal-framework-for-impact/a-legal-framework-for-impact.pdf

(emphasis added).

24 Id. (emphasis added).

25 Gordon, Jeffrey N., “Systematic Stewardship”

(January 24, 2022), Journal of Corporation Law, 2022 (Forthcoming), available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3782814 (emphasis

added).

26 YUM! Brands 2022 Proxy Statement, available at https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1041061/000119312522100360/d158301ddef14a.htm.

| · | “The challenge of individual costs and widely distributed societal benefits, a situation

common in many sustainability issues, plays a key role in antimicrobial resistance. This may make it difficult to pursue AMR mitigation

while remaining competitive on costs and highlights the need for strong collaboration between both the public and private sectors.” |

| · | “Yum!’s efforts to impact this through lobbying, political influence, educational activities

and other expenditures could support a positive impact on the feasibility of AMR mitigation efforts moving forward.”27 |

Economic impact estimates for AMR are stark, with a 2017 World Bank

study projecting costs by the year 2050 of up to 3.8 percent of global GDP, an impact comparable to the 2008 global financial crisis.28

Notably, this is likely a significant underestimate, as it relied on studies at the time that estimated there had been roughly 700,000

annual deaths from AMR since 2014 and predicted those deaths would rise to 10 million by 2050 if no action were taken. A 2022 study published

in The Lancet revised AMR-associated deaths significantly upward, determining that between 1.27 million and 4.95 million deaths

in 2019 were associated with bacterial AMR.29 It stands to reason, then, that the economic impact by 2050 will be considerably

worse than the World Bank projections cited above. It is a virtual certainty that any marginal increase in alpha YUM! Brands may generate

through antibiotics overuse will be a rounding error compared to the economic damage from AMR that will drag down the value of BlackRock

clients’ diversified portfolios.

The message is clear: to optimize returns, fiduciaries such as BlackRock

must exercise their governance rights and other prerogatives to protect themselves and their clients from individual companies that threaten

beta.

_____________________________

27 2021 YUM! Antimicrobial Resistance Report, available

at https://www.yum.com/wps/wcm/connect/yumbrands/41a69d9d-5f66-4a68-bdee-e60d138bd741/Antimicrobial+Resistance+Report+2021+11-4+-+final.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=nPMkceo.

28 World Bank, “Drug-Resistant Infections: A Threat

to Our Economic Future,” (March 2017), available at

https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/323311493396993758/pdf/final-report.pdf.

29 Christopher JL Murray et al., “Global burden of

bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis,” The Lancet (January 19, 2022), available at https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)02724-0/fulltext#%20.

(“We estimated that, in 2019, 1.27 million deaths (95% uncertainty interval [UI] 0.911–1.71) were directly attributable to

resistance (ie, based on the counterfactual scenario that drug-resistant infections were instead drug susceptible) in the 88 pathogen–drug

combinations evaluated in this study. On the basis of a counterfactual scenario of no infection, we estimated that 4.95 million deaths

(3.62–6.57) were associated with bacterial AMR globally in 2019 (including those directly attributable to AMR).”)

F. In

its Opposition Statement, BlackRock either fails to understand or refuses to acknowledge the point

BlackRock asserts the Proposal is illegal. As shown above, that claim,

previously rejected by the SEC Staff, does not hold water and is contrary to legal scholarship. Furthermore:

1. BlackRock

seems to miss the fact that the Proposal focuses narrowly on investor interests

At several points in its Opposition Statement, BlackRock raises “stakeholder”

interests, apparently having missed the point that this Proposal pertains squarely to improving investment returns. BlackRock says it

“believe[s] that companies that create value for their full range of stakeholders are better placed to deliver long-term value for

their shareholders, and this principle of stakeholder capitalism is already reflected in our stewardship guidelines.” While

we certainly value corporate attention to stakeholder interests, that is not the point of this Proposal. As we have explained at length,

this Proposal seeks a change in BlackRock’s stewardship practices that would benefit its own clients, to whom the Company has

fiduciary obligations.

2. BlackRock

says it offers custom voting options, again dodging the Proposal’s central point

BlackRock points to the fact that it has recently made it possible

for “institutional clients to participate in proxy voting decisions,” which it says “empower[s] clients who would like

to vote their holdings in a manner consistent with the views of the proponent to exercise their choice and vote proxies themselves.”

While some clients may choose to exercise more control over some of their votes, it seems likely that, for the foreseeable future, BlackRock

will retain voting power over the shares of many of its clients, including retail investors in its mutual funds and ETFs, and will continue

to engage in stewardship work beyond mere voting. For clients who either do not choose to vote their positions or who are not offered

the option, and for all clients affected by its other stewardship activities, it is critical that BlackRock adopt stewardship policies

that recognize the critical role beta plays in their investments.

G. Why

you should vote “FOR” the Proposal

Voting “FOR” the Proposal will show that shareholders

want BlackRock to stop putting its clients’ diversified portfolios at risk by artificially mandating that its stewardship policies

aim to maximize financial return at individual companies.

Additionally:

| · | BlackRock’s focus on maximizing individual company value not only threatens the diversified portfolios of its clients, but also

the diversified portfolios of its shareholders, who also rely on healthy social and environmental systems to support their investments

over the long term. |

| · | BlackRock’s decision-makers—who are heavily compensated in equity—do not share the same broad market risk

as BlackRock’s diversified shareholders. |

Conclusion

Vote “FOR” Item 4

By voting “FOR” Item 4, shareholders can urge BlackRock

to ensure its stewardship practices do not threaten the returns of diversified clients and shareholders. This will help the BlackRock

Board and management to authentically serve the needs of clients while preventing the dangerous implications to shareholders and others

of a narrow focus on financial return.

The Shareholder Commons urges you to vote FOR Item 4 on the

proxy, the Shareholder Proposal requesting shift in stewardship policies in favor of diversified shareholder value at the BlackRock Inc.

Annual Meeting on May 25, 2022.

For questions regarding the BlackRock Inc. Proposal submitted by

James McRitchie, please contact Sara E. Murphy, The Shareholder Commons at +1.202.578.0261 or via email at sara@theshareholdercommons.com.

THE FOREGOING INFORMATION MAY BE DISSEMINATED

TO SHAREHOLDERS VIA TELEPHONE, U.S. MAIL, E-MAIL, CERTAIN WEBSITES, AND CERTAIN SOCIAL MEDIA VENUES, AND SHOULD NOT BE CONSTRUED AS INVESTMENT

ADVICE OR AS A SOLICITATION OF AUTHORITY TO VOTE YOUR PROXY.

PROXY CARDS WILL NOT BE ACCEPTED BY FILER NOR

BY THE SHAREHOLDER COMMONS.

TO VOTE YOUR PROXY FOLLOW THE INSTRUCTIONS ON

YOUR PROXY CARD.

12

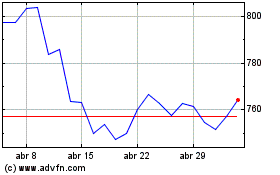

BlackRock (NYSE:BLK)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Mar 2024 até Abr 2024

BlackRock (NYSE:BLK)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Abr 2023 até Abr 2024