Roundup Plaintiffs' Lawyers Spar Over $800 Million in Fees

04 Março 2021 - 10:29AM

Dow Jones News

By Sara Randazzo

Plaintiffs' firms that led the legal campaign against Bayer AG

are fighting over $800 million in fees from the Roundup weedkiller

litigation, arguing that they deserve a bigger slice of one of the

largest-ever corporate settlements than firms that joined

later.

The high-stakes dispute is coming to the fore eight months after

Roundup's maker, Bayer, announced that it would pay up to $9.6

billion to resolve 125,000 cancer claims brought by dozens of law

firms. The fee fight underscores increasing tension between law

firms that do the in-court work necessary to win cases and those

that advertise to sign up scores of clients.

The Roundup deal isn't a single, all-encompassing pact that

needs signoff from a court but instead a series of confidential

settlements between Bayer and the many law firms with eligible

clients. Some of those firms spearheaded the litigation, but most

signed up clients later in the process, building on work already

started.

Six law firms appointed by a federal court as leaders in the

litigation are asking a judge to set aside 8.25% of the Bayer

settlements into a fund to be distributed among those firms and

others that handled the brunt of the work. Under their proposal,

those firms would get a share of the fund and reap whatever fees

they agreed upon with their clients. Plaintiffs' lawyers often take

a cut of more than 30% from such settlements.

The leadership firms, led by Andrus Wagstaff PC, Weitz &

Luxenberg PC and the Miller Firm, argue that they invested at least

$20 million and years of time to build a case linking Roundup to

cancer. They described the common-benefit fund as a sort of "tax"

on law firms that waited until the litigation was successful before

getting involved.

Several law firms have objected, saying the court doesn't have

the power to create the common fund -- estimated at $800 million.

They say the leadership team is trying to double-dip, speculating

that their confidential deals with Bayer are already more lucrative

than those that other firms received.

"They've already been adequately compensated multiple times

over," Melissa Ephron, a Texas lawyer objecting to the extra fees,

said at a virtual court hearing on the matter Wednesday.

The confidential nature of Bayer's settlements means the public

is unlikely to know each law firm's take and how much money the

affected plaintiffs who blame their cancer on Roundup use will

personally receive.

Bayer hasn't conceded that its weedkiller can cause non-Hodgkin

lymphoma and will continue to sell the product without a

cancer-warning label.

U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria in San Francisco, who

oversees around 4,000 Roundup cases filed in federal court, raised

doubts Wednesday that he has the authority to require every law

firm striking a deal to give up 8.25%.

"They all got their settlements because you achieved such a good

result. There's no question about that," he said during the

hearing, but added that he wasn't convinced it was appropriate for

the leadership to get a windfall.

The fight highlights a dynamic playing out more in recent years

in large cases alleging harms from drugs or everyday products. A

sophisticated ecosystem of advertisers and marketers sign up

plaintiffs in bulk and pass them off to lawyers who file claims in

court, often with little vetting on the strength of the cases. The

rising number of plaintiffs can help pressure companies to

settle.

The lead lawyers for Roundup plaintiffs pointed to this dynamic

to bolster their argument for why they deserve more money than the

more than 500 other law firms with Roundup clients.

After the lead firms had some key early success in the

litigation, "a tsunami of advertising resulted in thousands of new

lawsuits filed by law firms that had hedged their bets," the

leadership team wrote in a January filing.

"To not tax lawyers who literally sit on the sidelines...would

be to incentivize lawyers to do nothing in the future...and wait

for the lawyers who do the litigation to bring it home," Robin

Greenwald, one of the lead lawyers, told Judge Chhabria

Wednesday.

The lead law firms began probing a link between Roundup and

non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 2015 after the International Agency for

Research on Cancer concluded that Roundup's active ingredient,

glyphosate, was "probably carcinogenic" in humans.

The lead firms say they obtained and organized millions of

internal documents from Monsanto Co., Roundup's creator, which was

later purchased by Bayer. They interviewed 35 Monsanto employees

and hundreds of others relevant to the litigation, found scientists

to attest to a link between the product and illness and won crucial

court approval allowing their scientific experts to testify to

juries. Their work, which for many of the lawyers was a full-time

job for years, they argue, led to three large jury verdicts in

California in favor of plaintiffs and momentum that resulted in the

settlement.

Bayer has been trying to cap its Roundup liabilities after years

of shareholder concern and sliding stock prices. It is still trying

to reach settlements with holdout law firms that are threatening to

push their cases to trial. The company also is seeking court

approval this month for a class-action that would resolve Roundup

cases that haven't yet been filed, including from people who have

used Roundup but not developed non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Write to Sara Randazzo at sara.randazzo@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 04, 2021 08:14 ET (13:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

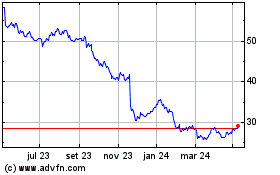

Bayer (TG:BAYN)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Fev 2025 até Mar 2025

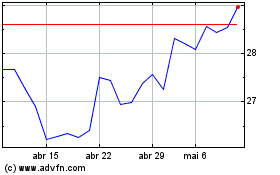

Bayer (TG:BAYN)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Mar 2024 até Mar 2025