By Christopher M. Matthews

Big oil companies endured one of their worst second quarters

ever and are positioning themselves for prolonged pain as the

coronavirus pandemic continues to sap global demand for fossil

fuels.

Exxon Mobil Corp. posted a quarterly loss for the second

straight quarter for the first time this century on Friday,

reporting a loss of $1.1 billion, compared with a profit of $3.1

billion a year ago. Exxon, the largest U.S. oil company, hadn't

reported back-to-back losses for at least 22 years, according to

Dow Jones Market Data, whose figures extend to 1998.

"The global pandemic and oversupply conditions significantly

impacted our second-quarter financial results with lower prices,

margins, and sales volumes," Exxon Chief Executive Darren Woods

said.

Chevron Corp. said Friday it lost $8.3 billion in the second

quarter, down from $4.3 billion in profits during the same period

last year, its largest loss since at least 1998. It wrote down $5.7

billion in oil-and-gas properties, including $2.6 billion in

Venezuela, citing uncertainty in the country ruled by strongman

Nicolás Maduro. Chevron also said it lowered its internal estimates

for future commodity prices.

Royal Dutch Shell PLC and Total SA reported significant losses

in the second quarter earlier this week, as the impact of the

pandemic and a worsening long-term outlook for commodity prices

spurred them to write down the value of their assets.

The dismal results are ratcheting up the problems for the oil

giants, which were struggling to attract investors even before the

pandemic, as concerns over climate-change regulations and

increasing competition from renewable energy and electric vehicles

cloud the future for fossil fuels.

Holdings of oil-and-gas stocks by active money managers are at a

15-year low, according to investment bank Evercore ISI. BP PLC,

Shell and Total are all trading at 30-year lows relative to the

overall S&P 500. Exxon is trading at its lowest level to the

S&P 500 since 1977, according to the bank.

Many of the big oil companies have sought to retain investors

despite slowing growth and profits over the past decade by paying

out hefty dividends, but those payouts are proving hard to sustain

during the pandemic.

Crude prices have stabilized at around $40 a barrel, providing

modest relief for the industry after U.S. oil prices briefly turned

negative for the first time ever in April. But none of the world's

largest oil companies now foresee a rapid recovery as countries

continue to struggle with containing the coronavirus.

Chevron CEO Mike Wirth said his company faced an uncertain

future for energy demand and couldn't predict commodity prices with

confidence right now.

"We expect a choppy economy and a choppy market," Mr. Wirth said

in an interview earlier in July. "It all depends on the virus and

the policies enacted to respond to it."

Oil and gas production by both Exxon and Chevron decreased in

the quarter, down 7% and 3%, respectively, from a year ago, as the

companies shut off wells to avoid selling into a weak market.

Exxon's production-and-exploration business lost $1.7 billion,

which Exxon attributed to lower commodity prices. Chevron's

production unit lost $6.1 billion.

U.S. oil prices closed below $40 per barrel Thursday for the

first time in three weeks.

For the entire second quarter, U.S. oil prices averaged $28 per

barrel and Brent crude averaged about $33, according to Dow Jones

Market Data, prices at which even the largest oil companies

struggle to turn a profit, analysts say.

While major stock indexes have recovered from April, when they

fell to their lowest levels in years, oil and gas stocks have

continued to lag despite the slight rebound in commodity

prices.

Many of the world's largest energy companies, including Exxon

and Chevron, have for years used an integrated business model,

which has historically allowed them to weather most market

conditions.

By owning oil and gas wells, along with the downstream plants to

manufacture refined products like gasoline and chemicals, the

companies were long able to capitalize in one sector of their

business, regardless of whether oil prices were high or low.

But that model has failed to deliver strong returns for most of

the past decade, as the world has faced a glut of fossil fuels

triggered in part by America's fracking boom, and it isn't

protecting the companies now, according to Evercore ISI analyst

Doug Terreson.

"A broad-based reassessment of the capital-management programs

at the big oils is required at this point," Mr. Terreson said.

Oil companies have been forced to take dramatic action to shore

up their finances in recent months, including cutting tens of

billions of dollars from their budgets and laying off thousands of

employees.

Exxon, which had previously disclosed a 30% cut to capital

expenditures in 2020, said on Friday it has "identified significant

potential for additional reductions" and said capital spending in

2021 will be lower than this year's spending.

Its steepest cuts have been to U.S. shale drilling, particularly

in the Permian Basin, the most active U.S. oil field, where it

removed half of its drilling rigs and will cut half of the

remaining 30 rigs by the end of year. Chevron is operating just

four rigs in the Permian and said production there would decline

around 7% this year.

Shell in April cut its dividend for the first time since World

War II to avoid having to borrow to fund it. It reported a

second-quarter loss of $18.4 billion on Thursday, which included a

$16.8 billion write-down, while French giant Total posted an $8.4

billion loss including an $8.1 billion write-down. Both companies

report net income attributable to shareholders, a proxy for net

profits. BP reports Tuesday.

Excluding impairments, Shell and Total actually turned a profit

during the quarter as their trading units helped stave off even

larger losses.

Exxon and Chevron have promised they will maintain their

dividends, viewed by many investors as the most attractive part of

owning their stocks. Some analysts predict Exxon may be forced to

cut its dividend in 2021 if market conditions don't recover.

Exxon's dividend payments cost the company almost $15 billion a

year. The company's debt grew by $8.8 billion in the quarter,

according to Goldman Sach Group Inc., which said Exxon will need

oil prices around $75 per barrel in 2021 to cover its dividend

payments from cash flow. Exxon said Friday it wouldn't take on

additional debt.

Dan Pickering, chief investment officer of energy investment

firm Pickering Energy Partners LP, said the industry can survive at

$40 oil but needs significantly higher prices to thrive. According

to Mr. Pickering, who said he holds small positions in Exxon and

Chevron, oil companies will have to continue cost-cutting for the

foreseeable future.

"You've got to assume that this is the world we're going to be

in, Mr. Pickering said. "And, if this is the world we're going to

be in, the cost structure is too high."

--Dave Sebastian contributed to this article.

Write to Christopher M. Matthews at

christopher.matthews@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 31, 2020 14:16 ET (18:16 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

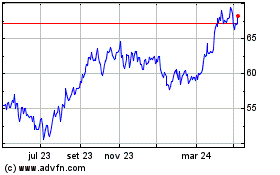

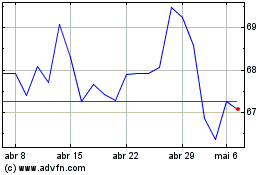

TotalEnergies (EU:TTE)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Out 2024 até Nov 2024

TotalEnergies (EU:TTE)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Nov 2023 até Nov 2024