US Oil-Field-Service Cos Push To Improve Fracking Efficiency

27 Junho 2011 - 2:22PM

Dow Jones News

With energy producers expected to spend a record amount of money

this year looking for and extracting oil and natural gas,

oil-field-service companies are being stretched thin.

Heightened demand, along with a desire to lower costs and lift

profit margins, have companies including Halliburton Co. (HAL) and

Schlumberger Ltd. (SLB) racing to become more efficient.

Weatherford International Ltd. (WFT), for example, is

introducing rubber and metal packing materials to replace

traditional cement well casings, which cause delays as crews wait

for them to cure. Halliburton, meanwhile, is tipping sand-filled

tractor trailers on end to save space at well sites and to allow

gravity, rather than diesel engines, to empty them of the material

used to prop open shale fractures.

"This is the time to invest in cutting our costs," Halliburton

Chief Financial Officer Mark McCollum told investors during a

recent conference. The efforts are focused particularly on reducing

the time and money needed to unlock unconventional fuel reservoirs

through horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, or fracking.

These recently developed techniques require a lot of manpower and

resources, and they play an increasing role in supplying the

world's energy needs.

What are known as the Big Four oil-field-services

companies--Halliburton, Schlumberger, Baker Hughes Inc. (BHI) and

Weatherford--have boosted their capital spending by 40% to keep

pace with producers and to develop resource-saving technology, said

James West, an analyst with Barclays Capital.

Still, West said, spare oil-field-service capacity "will mostly

be erased by the end of this year," as exploration and production

spending tops $500 billion.

Oil and natural-gas producers are already feeling the strain. In

some cases, they are waiting months between initial drilling into

shale formations and the arrival of hydraulic-fracturing equipment

needed to complete wells and start production. This has placed a

premium on how quickly service providers can perform fracking

services.

Schlumberger, for instance, touts new automated fracturing

technology that allows it to perform several tasks deep inside

wells with one tool instead of the several it used to take. By not

having to snake separate tools in and out of the miles-long well

bores, Schlumberger is able to complete fracking jobs that once

took 20 hours in half that time.

"We can save a full day of the [fracking] crew on the location

just because we can do things faster than they've been done

before," said Valerie Jochen, technical director for Schlumberger's

Unconventional Resources unit.

Weatherford is investing heavily in technology to study shale

formations before drilling begins so that only the most productive

areas are fractured, said Nicholas Gee, who heads the company's

reservoir and formation evaluation unit.

"Up to now, people have just generally drilled a well and then

fracked everything," Gee said.

Halliburton late last year launched an initiative to reduce

well-site personnel by 35% and to trim well-completion time by 25%

by 2013, measures aimed at cutting costs.

Some of the Houston company's efforts have involved developing

new technology, such as portable ultraviolet-light units designed

to eliminate pipe-corroding bacteria from fracking fluids. That

eliminates the need to using hundreds of thousands of gallons of

bacteria-killing chemicals. Other efforts have involved simply

rethinking the relatively mundane, such as turning the sand-filled

tractors on end, said David Adams, who heads Halliburton's

production-enhancement division.

"It's funny, but it was a novel concept," Adams said.

Delivering faster, more efficient fracturing not only helps

Halliburton meet surging demand for such services now but it

ensures that "we can still maintain margins as we go through

downturns," Adams said.

So far, Halliburton has been able to pass along to its customers

the cost increases that come when demand outstrips supply, he said.

But producers will probably be less accepting of price increases if

oil prices fall.

Producers can make money if oil drops as low as $60 a barrel,

but oil at $80 a barrel would affect cash flows enough that many

producers might reduce drilling, said Dahlman Rose & Co.

analyst James Crandell.

Oil has slid more than 20% from the $114-per-barrel highs seen

in April. On Monday, light, sweet crude oil for August delivery

recently traded 34 cents lower at $90.82 per barrel on the New York

Mercantile Exchange.

-By Ryan Dezember, Dow Jones Newswires; 713-547-9208;

ryan.dezember@dowjones.com

--Angel Gonzalez contributed to this article.

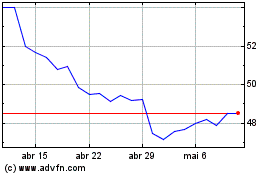

Schlumberger (NYSE:SLB)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Jun 2024 até Jul 2024

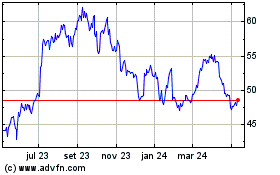

Schlumberger (NYSE:SLB)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Jul 2023 até Jul 2024