By Peter Loftus

NEW ORLEANS--A massive new study found that the pulse sensor in

Apple Inc.'s watch helped detect a heart-rhythm disorder in a small

number of users but may have caused false alarms for others.

The study's mixed findings hinted at the potential of "wearable"

gadgets to detect asymptomatic health conditions in people that

might otherwise go unnoticed. But doctors said the potential false

positives and other aspects of the study show that people should be

cautious about relying on the technology as diagnostic tools.

"The wearable sensors, I think we have a ways to go," Dr.

Richard Kovacs, professor of cardiology at Indiana University

School of Medicine and incoming president of the American College

of Cardiology, said in an interview at the ACC's annual meeting in

New Orleans, where the study was presented Saturday.

With funding from Apple, researchers from Stanford University

started the "Apple Heart Study" in 2017 and eventually enrolled

nearly 420,000 American adults who owned an Apple Watch and an

iPhone. A majority were under the age of 40, but nearly 25,000

people were at least 65 -- the primary at-risk age group for

irregular-heartbeat conditions.

Participants could enroll in the study by downloading an app on

the iPhone. The study is a sign of Apple's ambitions to push into

the large U.S. health-care market.

The optical pulse sensor on Apple's watch picks up heart rates,

and researchers explored whether that tool could detect irregular

heartbeats known as atrial fibrillation, a condition that can

increase one's risk for stroke.

Up to six million Americans are estimated to have atrial

fibrillation, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. Many don't experience symptoms, which can leave the

condition undetected. Patients can take blood-thinning drugs to try

to ward off strokes, though these drugs carry risks of causing

bleeding.

Participants in the Stanford study used older versions of

Apple's watch, not the latest version unveiled in September, which

added a built-in electrocardiogram to the pulse sensor.

In the study, if Apple's watch picked up suspected atrial

fibrillation, it displayed a written notification to the user.

Users could then use the study app on their iPhones to get a live

video consultation with doctors helping to run the study.

The doctors advised any participants experiencing serious

symptoms to get immediate treatment. But if there were no symptoms

beyond the watch notification, researchers mailed electrocardiogram

patches for participants to wear on their chests for one week, to

confirm whether they had atrial fibrillation. ECG's, traditionally

given in medical offices, record heart rhythm and electrical

activity and can more definitively diagnose atrial

fibrillation.

The study ended in August 2018. In all, only about 2,160 people,

or 0.5% of study participants, received notifications of irregular

heart rhythms. The rate was higher in people 65 and older -- 3.2%,

verus 0.16% in people ages 22 to 39.

Of those notified by the watch, only about 450 people received

and returned the wearable ECG patches to the researchers. Some

didn't get patches because they didn't call the study doctor, or

they revealed they had previously been diagnosed with atrial

fibrillation, which disqualified them from the study, said Marco

Perez, an associate professor of cardiovascular medicine at

Stanford and one of the study leaders, in an interview.

Researchers found that the ECG patches confirmed atrial

fibrillation in only 34% of the 450 people who returned patches.

The remaining two-thirds had no confirmed atrial fibrillation

during the time they wore the patches -- raising questions about

the watch's accuracy.

Renato Lopes, professor of at Duke University School of

Medicine, said the watch has potential to detect some

atrial-fibrillation cases "you would not get otherwise." But in a

panel discussion after results were presented, he said the 34%

confirmation rate was "not very high."

Dr. Perez of Stanford said episodes of atrial fibrillation can

be intermittent, which could help explain why a big proportion of

ECG patch wearers had no confirmed atrial fibrillation during the

week they wore it.

Doctors at the ACC meeting expressed concern that widespread use

of the watch would lead people to undergo unnecessary tests and

treatment, either because of false alarms or because they have

atrial fibrillation that carries a lower risk of complications.

Patients with lower-risk cases can be monitored instead of

immediately undergoing treatment with blood thinners, doctors

say.

"This also has the possibility to lead a lot of patients

potentially to being treated unnecessarily or prematurely, or

flooding doctors' offices and cardiologists' offices with a lot of

young people," Jeanne Poole, professor at the University of

Washington in Seattle, said during the panel discussion after the

results were presented

Cost is another issue: The latest versions of the watch start at

$399, while the previous model starts at $279. Doctors said more

research is needed on the cost-effectiveness of the use of the

watches to find heart problems.

Measured another way, Dr. Perez said the likelihood that the

watch detected atrial fibrillation as confirmed by the ECG patch

was 84%, but this analysis was conducted in a smaller group, among

86 participants who received positive watch notifications of

irregular heartbeats.

The Stanford researchers acknowledged the study's limitations --

it lacked a control arm and didn't track patient outcomes such as

stroke. And statistically, it didn't meet researchers' goals for

confidence in some of the key measures. But they said it is a start

in helping to assess the usefulness of wearable technologies.

"We've made some important measurements that are then going to

be able to be used by clinicians to help guide what they want to do

with the patient in front of them who has been notified," said Dr.

Perez.

Sumbul Desai, a Stanford professor and vice president of health

at Apple, said the watch's heartbeat tracker isn't intended to be a

diagnostic or screening tool. "I view the Apple Heart Study as just

a first step," she said in a panel discussion. She said Apple

planned further research to better understand the medical value of

the watch, including a new study in partnership with Johnson &

Johnson announced in January.

Write to Peter Loftus at peter.loftus@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 16, 2019 13:51 ET (17:51 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

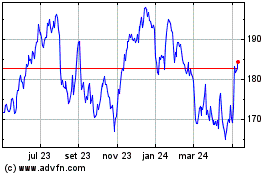

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Mar 2024 até Abr 2024

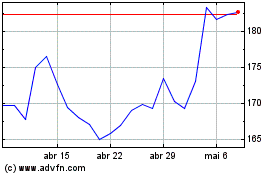

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Gráfico Histórico do Ativo

De Abr 2023 até Abr 2024